Will the Guilottine Be Used Again

The official guillotine used by the state of Luxembourg from 1789 to 1821

A guillotine ( GHIL-ə-teen, also GHEE-, French: [ɡijɔtin] ( ![]() listen )) is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at the lesser of the frame, positioning the neck directly below the blade. The blade is then released, swiftly and forcefully decapitating the victim with a single, make clean laissez passer so that the head falls into a handbasket or other receptacle below.

listen )) is an apparatus designed for efficiently carrying out executions by beheading. The device consists of a tall, upright frame with a weighted and angled blade suspended at the top. The condemned person is secured with stocks at the lesser of the frame, positioning the neck directly below the blade. The blade is then released, swiftly and forcefully decapitating the victim with a single, make clean laissez passer so that the head falls into a handbasket or other receptacle below.

The guillotine is best known for its employ in France, particularly during the French Revolution, where the revolution's supporters historic it as the people's avenger and the revolution'southward opponents vilified information technology as the pre-eminent symbol of the violence of the Reign of Terror.[i] While the name "guillotine" itself dates from this period, similar devices had been in use elsewhere in Europe over several centuries. The use of an oblique blade and the stocks set this blazon of guillotine apart from others. The display of severed heads had long been one of the well-nigh mutual ways European sovereigns exhibited their power to their subjects.[2]

The guillotine was invented with the intention of making majuscule punishment less painful in accordance with Enlightenment idea. Prior to the guillotine, France had previously used beheading along with many other methods of execution, many of which were essentially more gruesome and required some skill to exist done properly. Afterward its adoption, the device remained France'due south standard method of judicial execution until the abolition of capital letter punishment in 1981.[3] The last person to exist executed in France was Hamida Djandoubi, who was guillotined on ten September 1977.[ citation needed ] Djandoubi was the concluding person executed by guillotine past whatsoever government in the earth.[ commendation needed ]

Precursors [edit]

The use of beheading machines in Europe long predates such apply during the French Revolution in 1792. An early example of the principle is institute in the High History of the Holy Grail, dated to about 1210. Although the device is imaginary, its office is clear.[4] The text says:

Within these three openings are the hallows set for them. And behold what I would do to them if their 3 heads were therein ... She setteth her hand toward the openings and draweth forth a pivot that was fastened into the wall, and a cutting bract of steel droppeth down, of steel sharper than any razor, and closeth upwardly the three openings. "Even thus will I cutting off their heads when they shall set them into those three openings thinking to adore the hallows that are beyond."[4]

The Halifax Gibbet was a wooden structure consisting of 2 wooden uprights, capped past a horizontal beam, of a total pinnacle of 4.5 metres (15 ft). The bract was an axe head weighing three.five kg (seven.7 lb), fastened to the lesser of a massive wooden block that slid up and downwardly in grooves in the uprights. This device was mounted on a large square platform 1.25 metres (4 ft) high. Information technology is not known when the Halifax Gibbet was first used; the first recorded execution in Halifax dates from 1280, but that execution may take been by sword, axe, or gibbet. The machine remained in use until Oliver Cromwell forbade capital punishment for petty theft. It was used for the final time, for the execution of two criminals on a single solar day, on 30 Apr 1650.

A Hans Weiditz (1495-1537) woodcut illustration from the 1532 edition of Petrarch's De remediis utriusque fortunae, or "Remedies for Both Adept and Bad Fortune" shows a device similar to the Halifax Gibbet in the background existence used for an execution.

Holinshed's Chronicles of 1577 included a picture show of "The execution of Murcod Ballagh well-nigh Merton in Republic of ireland in 1307" showing a similar execution machine, suggesting its early use in Republic of ireland.[5]

The Maiden was constructed in 1564 for the Provost and Magistrates of Edinburgh, and was in apply from April 1565 to 1710. One of those executed was James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton, in 1581, and a 1644 publication began circulating the legend that Morton himself commissioned the Maiden later on he had seen the Halifax Gibbet.[6] The Maiden was readily dismantled for storage and ship, and it is now on display in the National Museum of Scotland.[7]

France [edit]

Etymology [edit]

For a menstruum of fourth dimension after its invention, the guillotine was called a louisette. However, it was later named after French physician and Freemason Joseph-Ignace Guillotin, who proposed on 10 October 1789 the use of a special device to carry out executions in France in a more humane manner. A death sentence opponent, he was displeased with the breaking wheel and other mutual and gruesome methods of execution and sought to persuade Louis XVI of France to implement a less painful alternative. While not the device's inventor, Guillotin's proper name ultimately became an eponym for it. The beliefs that Guillotin invented the device and that he was later executed by it are not true.[viii]

Invention [edit]

French surgeon and physiologist Antoine Louis, together with German engineer Tobias Schmidt, built a prototype for the guillotine. Co-ordinate to the memoires of the French executioner Charles-Henri Sanson, Louis XVI suggested the use of a straight, angled blade instead of a curved ane.[ix]

Introduction in France [edit]

On x October 1789, physician Joseph-Ignace Guillotin proposed to the National Assembly that capital penalty should always take the form of decapitation "by means of a simple mechanism".[10]

Sensing the growing discontent, Louis 16 banned the use of the breaking wheel.[11] In 1791, every bit the French Revolution progressed, the National Assembly researched a new method to be used on all condemned people regardless of class, consistent with the idea that the purpose of death penalty was but to end life rather than to inflict unnecessary pain.[11]

A commission formed under Antoine Louis, dr. to the King and Secretarial assistant to the Academy of Surgery.[11] Guillotin was also on the committee. The group was influenced by beheading devices used elsewhere in Europe, such as the Italian Mannaia (or Mannaja, which had been used since Roman times), the Scottish Maiden, and the Halifax Gibbet (3.v kg).[12] While many of these prior instruments crushed the neck or used blunt force to take off a head, devices likewise normally used a crescent blade to decollate likewise equally a hinged two-part yoke to immobilize the victim'south neck.[xi]

Laquiante, an officer of the Strasbourg criminal courtroom,[13] designed a beheading automobile and employed Tobias Schmidt, a High german engineer and harpsichord maker, to construct a prototype.[14] Antoine Louis is also credited with the design of the prototype. France'due south official executioner, Charles-Henri Sanson, claimed in his memoirs that King Louis XVI (an amateur locksmith) recommended that the device employ an oblique blade rather than a crescent one, lest the blade not be able to cut through all necks; the neck of the king, who would eventually die past guillotine years later, was offered upwards discreetly every bit an case.[15] The first execution past guillotine was performed on highwayman Nicolas Jacques Pelletier[16] on 25 April 1792[17] [eighteen] [nineteen] in front of what is at present the city hall of Paris (Place de fifty'Hôtel de Ville). All citizens condemned to die were from then on executed there, until the scaffold was moved on 21 Baronial to the Place du Carrousel.

The machine was deemed successful because it was considered a humane grade of execution in contrast with the more cruel methods used in the pre-revolutionary Ancien Régime. In France, before the invention of the guillotine, members of the nobility were beheaded with a sword or an axe, which often took two or more blows to kill the condemned. The condemned or their families would sometimes pay the executioner to ensure that the blade was sharp in social club to attain a quick and relatively painless death. Commoners were usually hanged, which could take many minutes. In the early on stage of the French Revolution earlier the guillotine's adoption, the slogan À la lanterne (in English language: To the lamp post! String Them Up! or Hang Them!) symbolized popular justice in revolutionary French republic. The revolutionary radicals hanged officials and aristocrats from street lanterns and also employed more than gruesome methods of execution, such as the wheel or burning at the stake.

Having but i method of civil execution for all regardless of form was also seen as an expression of equality amongst citizens. The guillotine was then the only civil legal execution method in France until the abolition of the death penalty in 1981,[xx] apart from certain crimes against the security of the land, or for the decease sentences passed by military courts,[21] which entailed execution by firing squad.[22]

Reign of Terror [edit]

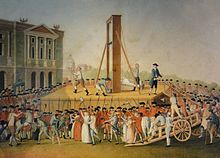

The execution of Louis 16

The execution of Robespierre. Notation that the person who has just been executed in this drawing is Georges Couthon; Robespierre is the figure marked "ten" in the tumbrel, holding a handkerchief to his shattered jaw.

Louis Collenot d'Angremont was a royalist famed for having been the first guillotined for his political ideas, on 21 August 1792. During the Reign of Terror (June 1793 to July 1794) well-nigh 17,000 people were guillotined. Former King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette were executed at the guillotine in 1793. Towards the end of the Terror in 1794, revolutionary leaders such as Georges Danton, Saint-Just and Maximilien Robespierre were sent to the guillotine. Most of the time, executions in Paris were carried out in the Place de la Revolution (one-time Identify Louis Xv and current Place de la Concorde); the guillotine stood in the corner virtually the Hôtel Crillon where the Metropolis of Brest Statue can exist found today. The machine was moved several times, to the Identify de la Nation and the Place de la Bastille, but returned, peculiarly for the execution of the Male monarch and for Robespierre.

For a fourth dimension, executions by guillotine were a popular grade of entertainment that attracted great crowds of spectators, with vendors selling programs list the names of the condemned. But more than than existence pop entertainment alone during the Terror, the guillotine symbolized revolutionary ideals: equality in death equivalent to equality before the police; open and demonstrable revolutionary justice; and the destruction of privilege under the Ancien Régime, which used split up forms of execution for nobility and commoners.[23] The Parisian sans-culottes, then the popular public face of lower-course patriotic radicalism, thus considered the guillotine a positive force for revolutionary progress.[24]

Retirement [edit]

Public execution on Guillotine; Flick taken on 20 April 1897, in front end of the jailhouse of Lons-le-Saunier, Jura. The homo who was going to be beheaded was Pierre Vaillat, who killed two elder siblings on Christmas day, 1896, in order to rob them and was condemned for his crimes on 9 March 1897.

Subsequently the French Revolution, executions resumed in the metropolis middle. On 4 Feb 1832, the guillotine was moved behind the Church of Saint-Jacques-de-la-Boucherie, just before being moved again, to the Grande Roquette prison, on 29 November 1851.

In the belatedly 1840s, the Tussaud brothers Joseph and Francis, gathering relics for Madame Tussauds wax museum, visited the anile Henry-Clément Sanson, grandson of the executioner Charles-Henri Sanson, from whom they obtained parts, the knife and lunette, of one of the original guillotines used during the Reign of Terror. The executioner had "pawned his guillotine, and got into woeful problem for alleged trafficking in municipal belongings".[25]

On 6 August 1909, the guillotine was used at the junction of the Boulevard Arago and the Rue de la Santé, behind the La Santé Prison.

The final public guillotining in France was of Eugen Weidmann, who was bedevilled of six murders. He was beheaded on 17 June 1939 outside the prison house Saint-Pierre, rue Georges Clemenceau five at Versailles, which is at present the Palais de Justice. Numerous bug with the proceedings arose: inappropriate behavior past spectators, incorrect assembly of the appliance, and secret cameras filming and photographing the execution from several storeys above. In response, the French regime ordered that hereafter executions exist conducted in the prison courtyard in private.[ commendation needed ]

The guillotine remained the official method of execution in French republic until the death penalty was abolished in 1981.[iii] The concluding 3 guillotinings in French republic before its abolition were those of kid-murderers Christian Ranucci (on 28 July 1976) in Marseille, Jérôme Carrein (on 23 June 1977) in Douai and torturer-murderer Hamida Djandoubi (on 10 September 1977) in Marseille. Djandoubi's death was the last time that the guillotine was used for an execution by whatever government.

Frg [edit]

In Germany, the guillotine is known equally the Fallbeil ("falling axe") and was used in diverse German states from the 19th century onwards,[ citation needed ] becoming the preferred method of execution in Napoleonic times in many parts of the state. The guillotine and the firing team were the legal methods of execution during the era of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the Weimar Commonwealth (1919–1933).

The original German guillotines resembled the French Berger 1872 model, but they eventually evolved into sturdier and more efficient machines. Congenital primarily of metal instead of wood, these new guillotines had heavier blades than their French predecessors and thus could use shorter uprights also. Officials could as well conduct multiple executions faster, thanks to a more efficient blade recovery system and the eventual removal of the tilting board (bascule). Those deemed probable to struggle were backed slowly into the device from behind a curtain to preclude them from seeing it prior to the execution. A metal screen covered the bract as well in social club to muffle it from the sight of the condemned.

Nazi Germany used the guillotine between 1933 and 1945 to execute xvi,500 prisoners – 10,000 of them in 1944 and 1945 alone.[26] [27] One political victim the government guillotined was Sophie Scholl, who was convicted of high treason after distributing anti-Nazi pamphlets at the University of Munich with her brother Hans, and other members of the German language student resistance group, the White Rose.[28] The guillotine was concluding used in West Germany in 1949 in the execution of Richard Schuh[29] and was final used in Due east Deutschland in 1966 in the execution of Horst Fischer.[thirty] The Stasi used the guillotine in East Germany between 1950 and 1966 for hugger-mugger executions.[31]

Elsewhere [edit]

A number of countries, primarily in Europe, continued to utilise this method of execution into the 19th and 20th centuries, but they ceased to use information technology before France did in 1977.

In Antwerp, the last person to be beheaded was Francis Kol. Convicted of robbery and murder, he received his penalization on viii May 1856. During the flow from 19 March 1798 to xxx March 1856, in that location were 19 beheadings in Antwerp.[32]

In Switzerland, it was used for the last time by the canton of Obwalden in the execution of murderer Hans Vollenweider in 1940.

In Hellenic republic, the guillotine (forth with the firing team) was introduced as a method of execution in 1834; it was terminal used in 1913.

In Sweden, beheading became the mandatory method of execution in 1866. The guillotine replaced manual beheading in 1903, and it was used only once, in the execution of murderer Alfred Ander in 1910 at Långholmen Prison, Stockholm. Ander was as well the last person to be executed in Sweden earlier death sentence was abolished in that location in 1921.[33] [34]

In Southward Vietnam, after the Diệm regime enacted the ten/59 Decree in 1959, mobile special military courts were dispatched to the countryside in order to intimidate the rural population; they used guillotines, which had belonged to the former French colonial power, in society to carry out death sentences on the spot.[35] One such guillotine is still on show at the State of war Remnants Museum in Ho Chi Minh City.[36]

In the Western Hemisphere, the guillotine saw only express utilize. The only recorded guillotine execution in Northward America north of the Caribbean area took place on the French island of St. Pierre in 1889, of Joseph Néel, with a guillotine brought in from Martinique.[37] In the Caribbean, information technology was used quite rarely in Guadeloupe and Martinique, the last time in Fort-de-France in 1965.[38] In South America, the guillotine was simply used in French Guiana, where most 150 people were beheaded betwixt 1850 and 1945: almost of them were convicts exiled from France and incarcerated inside the "bagne", or penal colonies. Within the Southern Hemisphere, information technology worked in New Caledonia (which had a bagne too until the cease of the 19th century) and at to the lowest degree twice in Tahiti.

In 1996 in the United States, Georgia Land Representative Doug Teper unsuccessfully sponsored a bill to replace that state'southward electric chair with the guillotine.[39] [forty]

In contempo years, a express number of individuals have died past suicide using a guillotine which they had constructed themselves.[41] [42] [43] [44]

Controversy [edit]

Retouched photo of the execution of Languille in 1905. Foreground figures were painted in over a real photograph.

Always since the guillotine's first use, there has been debate equally to whether or not the guillotine provided as swift and painless a expiry equally Guillotin had hoped. With previous methods of execution that were intended to be painful, few expressed concern almost the level of suffering that they inflicted. All the same, considering the guillotine was invented specifically to be more than humane, the issue of whether or not the condemned experiences hurting has been thoroughly examined and has remained a controversial topic. While certain eyewitness accounts of guillotine executions suggest anecdotally that sensation may persist momentarily after decapitation, there has never been true scientific consensus on the thing.

Living heads [edit]

The question of consciousness or awareness following decapitation remained a topic of discussion during the guillotine's utilise.

The following written report was written past Dr. Beaurieux, who observed the caput of executed prisoner Henri Languille, on 28 June 1905:

Hither, and then, is what I was able to notation immediately after the decapitation: the eyelids and lips of the guillotined human being worked in irregularly rhythmic contractions for well-nigh five or half-dozen seconds. This phenomenon has been remarked past all those finding themselves in the same weather as myself for observing what happens after the severing of the neck ...

I waited for several seconds. The spasmodic movements ceased. [...] It was then that I called in a strong, sharp voice: "Languille!" I saw the eyelids slowly elevator up, without any spasmodic contractions – I insist advisedly on this peculiarity – only with an even move, quite distinct and normal, such as happens in everyday life, with people awakened or torn from their thoughts.

Next Languille's eyes very definitely fixed themselves on mine and the pupils focused themselves. I was not, and so, dealing with the sort of vague deadening wait without any expression, that can exist observed whatever day in dying people to whom one speaks: I was dealing with undeniably living eyes which were looking at me. After several seconds, the eyelids closed again [...].

Information technology was at that point that I called out again and, again, without any spasm, slowly, the eyelids lifted and undeniably living eyes stock-still themselves on mine with perchance even more than penetration than the first fourth dimension. And so there was a further endmost of the eyelids, but now less complete. I attempted the issue of a third phone call; at that place was no further movement – and the eyes took on the glazed expect which they have in the dead.[45] [46]

Names for the guillotine [edit]

During the bridge of its usage, the French guillotine has gone by many names, some of which include:

- La Monte-à-regret (The Regretful Climb)[47] [48]

- Le Rasoir National (The National Razor)[48]

- Le Vasistas or La Lucarne (The Fanlight)[48] [49]

- La Veuve (The Widow)[48]

- Le Moulin à Silence (The Silence Mill)[48]

- Louisette or Louison (from the proper noun of paradigm designer Antoine Louis)[48]

- Madame La Guillotine[50]

- Mirabelle (from the name of Mirabeau)[48]

- La Bécane (The Auto)[48]

- Le Massicot (The Paper Trimmer)[49]

- La Cravate à Capet (Capet'due south Necktie, Capet being Louis XVI)[49]

- La Raccourcisseuse Patriotique (The Patriotic Shortener)[49]

- La demi-lune (The Half-Moon)[49]

- Les Bois de Justice (Timbers of Justice)[49]

- La Bascule à Charlot (Charlot's Rocking-chair)[49]

- Le Prix Goncourt des Assassins (The Goncourt Prize for Murderers)[49]

See also [edit]

- Bals des victimes

- Upper-case letter punishment in France

- Halifax Gibbet

- Henri Désiré Landru

- Rozalia Lubomirska

- Marcel Petiot

- Plötzensee Prison house

- Jozef Raskin

- Utilize of death penalty by nation

- Eugen Weidmann

References [edit]

- ^ R. Po-chia Hsia, Lynn Hunt, Thomas R. Martin, Barbara H. Rosenwein, and Bonnie G. Smith, The Making of the West, Peoples and Culture, A Concise History, Volume II: Since 1340, Second Edition (New York: Bedford/St. Martin'southward, 2007), 664.

- ^ Janes, Regina. "Beheadings." Representations No. 35.Special Result: Awe-inspiring Histories(1991):21–51. JSTOR. Web. 26 Feb. 2015. Pg 24

- ^ a b (in French) Loi n°81-908 du 9 octobre 1981 portant abolitionism de la peine de mort Archived 31 July 2013 at the Wayback Motorcar. Legifrance.gouv.fr. Retrieved on 2013-04-25.

- ^ a b High History of the Grail, translated by Sebastian Evans ISBN 9781-4209-44075

- ^ History of the guillotine Archived 6 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, The Guillotine Headquarters 2014.

- ^ Maxwell, H Edinburgh, A Historical Study, Williams and Norgate (1916), pp. 137, 299–303.

- ^ "The Maiden". Nms.air conditioning.britain. National Museums Scotland. Retrieved ii August 2019.

- ^ "Origins of the Guillotine". Snopes.com . Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- ^ Sanson, Charles-Henri (1831). Mémoires de Sanson. Tôme 3. pp. 400–408.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location (link) - ^ R. F. Opie (2003) Guillotine, Gloucestershire: Sutton Publishing Ltd, p. 22, ISBN 0750930349.

- ^ a b c d Executive Producer Don Cambou (2001). Modern Marvels: Death Devices. A&East Television Networks.

- ^ Parker, John William (26 July 1834). "The Halifax Gibbet-Police". The Sat Magazine (132): 32.

- ^ Croker, John Wilson (1857). Essays on the early on period of the French Revolution. J. Murray. p. 549. Retrieved 21 October 2010.

- ^ Edmond-Jean Guérin, "1738–1814 – Joseph-Ignace Guillotin : biographie historique d'une figure saintaise" Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Car, Histoire P@ssion website, accessed 2009-06-27, citing M. Georges de Labruyère in le Matin, 22 Aug. 1907

- ^ Memoirs of the Sansons, from individual notes and documents, 1688–1847 / edited by Henry Sanson. pp 260–261. "Memoirs of the Sansons, from individual notes and documents, 1688-1847 / Edited by Henry Sanson". 1876. Archived from the original on 11 May 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014. accessed 28 April 2016

- ^ "Crime Library". National Museum of Law-breaking & Punishment. Archived from the original on ane February 2009. Retrieved thirteen June 2009.

[I]north 1792, Nicholas-Jacques Pelletier became the get-go person to be put to decease with a guillotine.

- ^ Hunt's Calendar of Events 2007 . New York: McGraw-Hill. 2007. p. 291. ISBN978-0-07-146818-3.

- ^ Scurr, Ruth (2007). Fatal Purity. New York: H. Holt. pp. 222–223. ISBN978-0-8050-8261-half-dozen.

- ^ Abbott, Jeffery (2007). What a Style to Become . New York: St. Martin's Griffin. p. 144. ISBN978-0-312-36656-8.

- ^ Pre-1981 penal lawmaking, commodity 12: "Whatsoever person sentenced to death shall be beheaded."

- ^ Pre-1971 Code de Justice Militaire, article 336: "Les justiciables des juridictions des forces armées condamnés à la peine capitale sont fusillés dans un lieu désigné par l'autorité militaire."

- ^ Pre-1981 penal lawmaking, article 13: "By exception to article 12, when the capital punishment is handed for crimes against the safe of the State, execution shall have place by firing squad.".

- ^ Arasse, Daniel (1989). "The Guilloine and the Terror". London: Penguin. pp. 75–76.

- ^ Higonnet, Patrice (2000). "Goodness Beyond Virtue: Jacobins During the French Revolution ". Cambridge, MA: Harvard. p. 283.

- ^ Leonard Cottrell (1952) Madame Tussaud, Evans Brothers Limited, pp. 142–43.

- ^ Robert Frederick Opie (2013). Guillotine: The Timbers of Justice. History Printing. p. 131. ISBN9780752496054.

- ^ "According to Nazi records, the guillotine was somewhen used to execute some 16,500 people between 1933 and 1945, many of them resistance fighters and political dissidents." https://www.history.com/news/8-things-you-may-not-know-near-the-guillotine

- ^ Scholl, Inge (1983). The White Rose: Munich, 1942–1943. Schultz, Arthur R. (Trans.). Middletown, CT: Wesleyan Academy Press. p. 114. ISBN978-0-8195-6086-5.

- ^ Rolf Lamprecht (five September 2011). Ich gehe bis nach Karlsruhe: Eine Geschichte des Bundesverfassungsgerichts – Ein SPIEGEL-Buch. Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt. p. 55. ISBN978-3-641-06094-7.

- ^ Jörg Osterloh; Clemens Vollnhals (xviii January 2012). NS-Prozesse und deutsche Öffentlichkeit: Besatzungszeit, frühe Bundesrepublik und DDR. Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 368. ISBN978-3-647-36921-one.

- ^ John O. Koehler (five August 2008). Stasi: The Untold Story of the East German language Secret Police. Basic Books. p. eighteen. ISBN9780786724413.

- ^ Gazet van Mechelen, 8 May 1956

- ^ Bolmstedt, Åsa (21 December 2006). "Änglamakerskan" [The affections maker]. Populär Historia (in Swedish). LRF Media. Archived from the original on 5 October 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Rystad, Johan K. (1 April 2015). "Änglamakerskan i Helsingborg dränkte åtta fosterbarn" [The affections maker in Helsingborg drowned eight foster intendance children]. Hemmets Journal (in Swedish). Egmont Grouping. Archived from the original on 8 December 2015. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ^ Nguyen Thi Dinh; Mai V. Elliott (1976). No Other Route to Accept: Memoir of Mrs Nguyen Thi Dinh. Cornell University Southeast Asia Program. p. 27. ISBN0-87727-102-X.

- ^ Farrara, Andrew J. (2004). Effectually the World in 220 Days: The Odyssey of an American Traveler Abroad. Buy Books. p. 415. ISBN0-7414-1838-10.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on i December 2017. Retrieved 21 Nov 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy every bit title (link) - ^ Wren, Christopher S. (27 July 1986). "A Fleck of France off the Declension of Canada". The New York Times. Archived from the original on one December 2017.

- ^ Kruzel, John (1 Nov 2013). "Bring Back the Guillotine". Slate . Retrieved thirty January 2020.

- ^ "Georgia House of Representatives – 1995/1996 Sessions HB 1274 – Capital punishment; guillotine provisions". The General Assembly of Georgia. Archived from the original on 4 October 2013. Retrieved iii October 2013.

- ^ "Guillotine death was suicide". BBC News. 24 April 2003. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- ^ Sulivan, Anne (sixteen September 2007). "Man kills himself with guillotine". The News Herald. Tennessee. Retrieved eleven September 2016.

- ^ Staglin, Douglas. "Russian engineer commits suicide with bootleg guillotine". USA Today . Retrieved xi September 2016.

- ^ Buncomber, Andrew (3 December 1999). "Guillotine used for suicide". The Independent. Archived from the original on 2 January 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ Dr. Beaurieux. "Report From 1905". The History of the Guillotine. Archived from the original on 25 January 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ Clinical Journal. Medical Publishing Company. 1898. p. 436.

- ^ abbaye de monte-à-regret : définition avec Bob, dictionnaire d'argot, fifty'autre trésor de la langue Archived 14 March 2014 at the Wayback Auto. Languefrancaise.net. Retrieved on 2013-04-25.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Joseph-Ignace GUILLOTIN (1738–1814) Archived xv December 2012 at the Wayback Automobile. Medarus.org. Retrieved on 2013-04-25.

- ^ a b c d due east f g h guillotine du XIVeme arrondissement Archived 8 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Ktakafka.free.fr. Retrieved on 2013-04-25.

- ^ Guillotine Archived iv October 2012 at the Wayback Automobile. Whonamedit. Retrieved on 2013-04-25.

Further reading [edit]

- Carlyle, Thomas. The French Revolution in Three Volumes, Book 3: The Guillotine. Charles C. Piffling and James Dark-brown (Footling Brownish). New York, NY, 1839. No ISBN. (Get-go Edition. Many reprintings of this important history have been done during the last two centuries.)

- John Wilson Croker (1853), History of the Guillotine (1st ed.), London: John Murray, Wikidata Q19040187

- Gerould, Daniel (1992). Guillotine; Its Legend and Lore. Blast Books. ISBN0-922233-02-0.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guillotine. |

- The Guillotine Headquarters with a gallery, history, proper name list, and quiz.

- Bois de justice History of the guillotine, construction details, with rare photos (English)

- Fabricius, Jørn. "The Guillotine Headquarters".

- Does the head remain briefly conscious later on decapitation (revisited)? (from The Straight Dope)

- Scientific American, "The Origin of the Guillotine", 17-Dec-1881, pp.392

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Guillotine

Belum ada Komentar untuk "Will the Guilottine Be Used Again"

Posting Komentar